Now that you have read about some of my learning experiences at vintage cast iron cookware auctions in part I of my blog series on auctions, you can venture forth with knowledge to help you avoid the same mistakes I made.

Here are more tips and considerations to help you be a savvy bidder and have a successful auction!

What expenses will you incur in addition to a winning bid price?

Before you start bidding, you need to know all of the expenses you will incur in addition to your bid price. It is very important to know the actual price you will end up paying (the “out-the-door” price, as they like to say in the car business); not just the successful bid amount.

Even if you purchase something at a decent “base” price, the price you end up paying might be much higher, as with my first big online purchase.

Carefully Read the Auction’s Terms and Conditions

Bidders are responsible for reading the auction house’s terms and conditions before bidding. Don’t bid if you disagree with the terms and conditions.

I have heard people complain about shipping, handling, or other charges tacked on to a winning bid price after they have placed a successful bid at an auction. The time to find out about these potential charges is before you bid.

When you read the terms and conditions, you will know those costs in advance, or at least have a good idea of what they will be. Call the auction house if you need help understanding the terms and conditions.

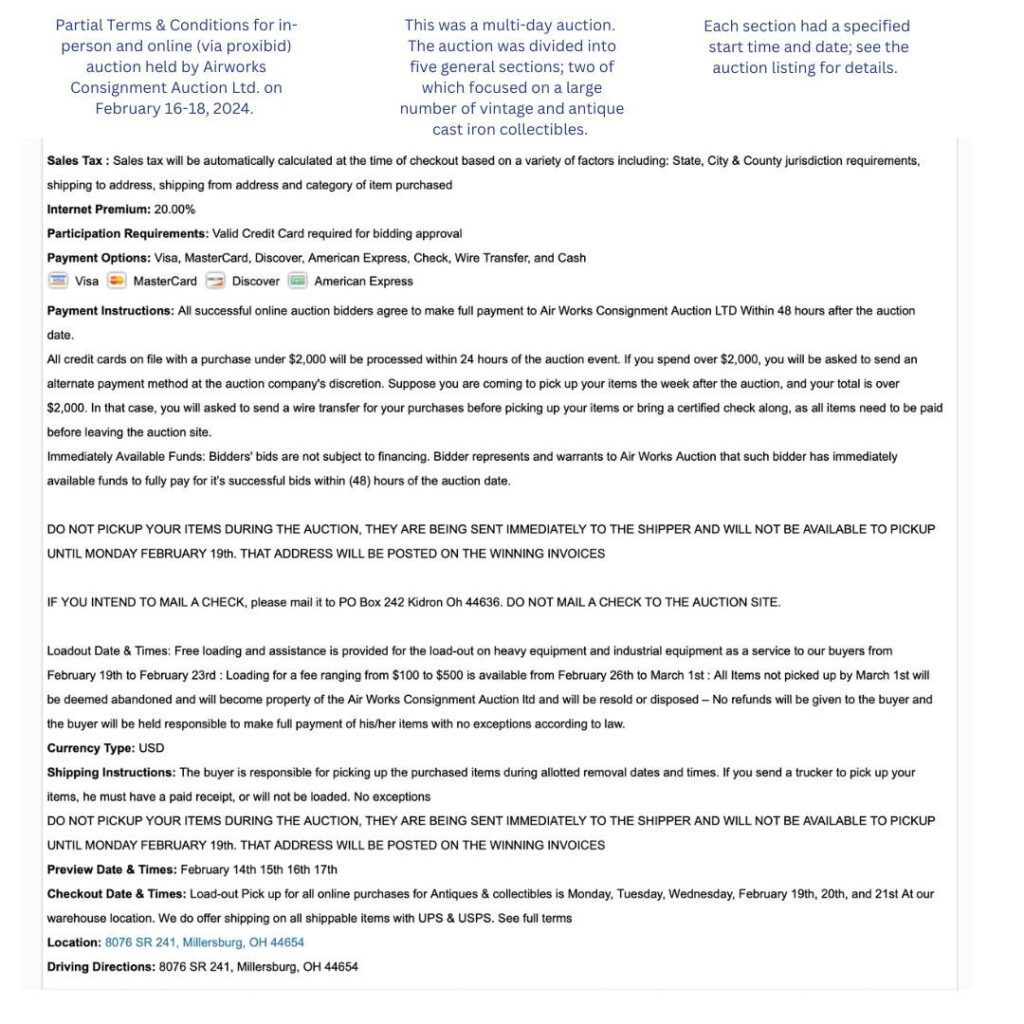

The photo at right shows an auction house’s terms and conditions for a multi-day auction held in February 2024 that contained many pieces of vintage and antique cast iron collectibles. Notice its length. Read it carefully.

Know the Buyer’s Premium

At most auctions, the auction house charges a “buyer’s premium” on items that you purchase. The buyer’s premium is added to your winning bid amount. You will find that the premium if you bid online is often higher than if you bid in person, presumably because the auction house has to pay a premium to have the auction online. You will find the buyer’s premium outlined in the auction terms and conditions.

When I started buying iron, the buyer’s premium was usually 10-15%. Today, it’s common to see buyer’s premiums of 20-25% or even more. If the buyer’s premium is 20% and you win at $100, you will pay $120 (before other costs such as tax and shipping and handling). Be sure to factor in this cost when deciding how much to bid for an item.

You may also pay sales tax on the piece if you do not have a sales tax exemption. Oddly enough, this is only sometimes the case. Check the auction terms and conditions to see whether this will be an added expense. Call the auction house if you need to learn more after reading the terms and conditions.

Know the Credit/Debit Card Premium

If you pay with a credit or debit card, you will likely see an additional amount (often 3.5-4%) tacked on to the winning bid price, presumably because the auction house has to pay a percentage to the credit card company when a credit card is used for purchase.

Some auction houses will ask for a credit card number up front; some won’t. Some allow you to pay at an in-person auction by credit or debit card; some don’t. Some will take a personal check; some require a bank check for purchases over a set amount.

The methods of payment will be in the auction’s terms and conditions.

Factor in Storage and Shipping Charges (or travel expenses!)

If you are bidding online, you will have to pay shipping charges. If you travel to the auction, factor in your travel expenses.

Cast iron is heavy and often oversized, of course, and it is always expensive to ship. If you need the auction house to hold a piece for pickup for a period of time, you may be required to pay a storage fee.

Shipping expenses can be to hundreds of dollars. You may not receive an exact shipping quote before you place a bid, so you will have to pay the actual packing and shipping charges even with only an estimated quote. In an online auction’s terms and conditions, you typically agree to cover the shipping cost by placing a bid.

Some auction houses have an independent vendor, such as UPS, come in to pack the items and ship them off, and other auction houses ship in-house, charging actual shipping costs plus (usually) a handling fee.

If the auction house uses an off-site shipping company (some will “recommend” packing/shipping companies and some will use a particular company), it will always be more expensive than if the shipping is done on-site. Read and understand the terms and conditions of the auction before you bid; it will tell you how shipping will be handled. If you don’t understand, call the auction house and ask.

Preview pieces

There is no substitute for in-person inspection of a piece before you buy.

The condition of an item dramatically affects its value, and it should heavily influence what you are willing to pay. All items at live auctions are sold “as is, where is.” This means there is no turning back once you’ve made the purchase. If you overlooked a defect during inspection, it doesn’t matter. You won’t be able to return the item; you are committed to the purchase. As a bidder, you must be fully aware of what you are buying; the auctioneer is not responsible.

Bidding online presents a challenge, as you can only physically inspect items after receipt. Instead, you must rely on photos, videos, and any description the auctioneer provides. The auctioneer may or may not be knowledgeable about vintage cast iron, may or may not know about reproductions, and may or may not notice or point out flaws. Best practice is to personally review any item you’d like to bid on.

A preview is usually offered a day or two before the auction opens or an hour or more before the auction begins. If the listing doesn’t say, call the auction house and ask.

During the preview look for flaws, recasts, and reproductions

When significant defects are discovered during preview at a sizeable cast iron auction, it is good practice for the person who found the imperfection to inform the auctioneer so that the auctioneer can inform other potential bidders.

While it may be “good practice,” however, that doesn’t mean it always happens. Again, as the bidder, you are responsible for knowing the piece’s condition before you bid.

During the preview at any auction, it is not uncommon to find hidden flaws. Hairline cracks may be discovered, or pitting or warpage noted that isn’t visible in the listing photos. 1 Sometimes, during the preview, people may notice a defect not listed in the auction catalog. Sometimes, there is no auction catalog, just a flyer that says “cast iron cookware” will be offered at a sale.

At a July 2019 auction I attended, auctioneer Bob Simmons noted all flaws and concerns discovered by potential bidders during the inspection. The Simmons team passed out a sheet of paper noting the problems before the auction, and they were also stated online as the auction took place.

Bear in mind that some auctioneers know vintage cast iron cookware and some don’t. Some auction houses might note in an auction listing whether a piece is warped and some might not. Sometimes fire damage or light pitting is visible only in person; not in the catalog’s black-and-white photos. It is not uncommon for hairline cracks to go unnoticed.

Remember, you as the bidder are assuming the risk.

The Auction

Register before the auction begins.

You are required to register before bidding, whether the auction is online or in-person. At a live auction, there will be an area where people take down your information. They will typically photocopy your driver’s license. They may take your payment information. You will be given a “paddle” – often a piece of card stock – with your bidder number prominently marked. That is how your bids will be matched to your auction wins.

If you are bidding online, you will need to register online and provide your payment information for the auction before it begins. Sometimes an auction house may put a dollar maximum on how much you can bid if you haven’t bid with them before.

While you can usually register during the auction (both in-person and online), it makes it much easier for the auction house if you do it before the auction begins. For an online auction, it can take some time before you are approved to bid.

Register in advance – you don’t want to miss your desired pieces!

Where to sit?

It seems like such a small thing, but…

Harold Henry usually sits in the front. He will sometimes look around to see who is bidding against him, but I think he doesn’t care much; if he sets out to get a piece, he will. Russ Howser is usually near the front but not in the front. Eric and Freda McAllister usually sit in the back, as does Vincent Warren, though sometimes Vincent stands and sometimes he sits. And sometimes, he disappears for a while. Brenda Bernstein and Doyle Pregler usually sit toward the back but not in the back. Chris Kendall is generally lurking around the back or darting around. I don’t think Chris sits much.

When I first started going to auctions I sat in the back so I could see who was bidding on what. That stopped when collector Sonny McCarter – who was helping with this particular auction by carrying pieces back to the winning bidders – pointed out that given the number of pieces I was buying, it would have been considerate of me to sit in a more accessible place rather than make him walk back and forth over and over again carrying heavy iron to me that I had won.

It’s a strategic dance, and people have their favorite spots. Sometimes people “reserve” a spot pre-auction by putting a piece of paper on a chair with their name on it. Since Sonny chided me, if I plan to buy much, I usually am somewhere in the middle, near or on an aisle. If Linda is with me, we often sit a few chairs apart so there is more room to place the iron we purchase. If a person buys many pieces, the auction house sometimes sets up a separate table for that person. At some auctions, won items are placed on tables organized by bidder number, while at other times, winning bidders are informed of a designated pickup time and place after the auction.

Know or have an idea of the bid increments

The auctioneer opens bidding on a particular piece by calling out a number that the auctioneer hopes will result in a starting bid, e.g. $50. If no one bids at $50, the auctioneer may drop the price in hopes that someone will bid on the lower amount.2 Occasionally, a person in the audience will yell out a price they are willing to pay. This can happen when a piece is particularly desirable and the auctioneer is starting very low. The bidder wants to get things moving, so yells out a higher number. This can also happen when no one is bidding on the auctioneer’s opening number – a person might yell out a lower price they are willing to pay and the auctioneer may start from there.

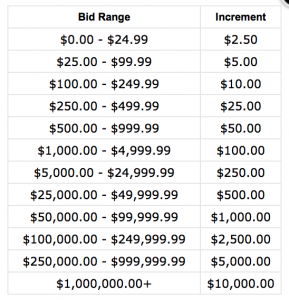

The auctioneer follows a bid increment schedule when chanting the dollar amounts. For example – as in the photo to the right – bid increments might be $2.50 up to $25 (e.g., $10, $12.50, $15, $17.50), then $5 to $100, etc. You will pick this up very quickly once bidding starts.

If you’ve never bid before, watch the auction before bidding to see how the particular auctioneer sets bid increments. Know, too, that bid increments are not set in stone. I have seen this happen often when two bidders fiercely bid against each other. For example, using the bidding increment chart above, if the bid is $550 and the competing bidder hesitates to bid $600, the auctioneer might drop the bid increment to $25 and ask for a $575 bid.

Set your limit before bidding begins

This is easier said than done; trust me, I know. It is very easy to get carried away at an auction and bid and/or buy more than you intended. I do it all the time.

Consider writing the maximum amount you are willing to bid for each item next to the item in the auction catalog, after you preview the item. Be sure to factor in the additional costs noted above when you set your maximum price.

Though I prefer not to do so, I have placed bids for friends who want something but cannot attend the auction. I always have them give me the maximum they are willing to pay, and I carefully inspect the piece before bidding. If I miss a flaw, my friend pays the price.

Only once have I had a friend say “buy it,” meaning “I don’t care how much it costs, I want it.” I bought it.

Do not bid first or in advance of the auction start

At an in-person auction, I never bid first. I don’t want to drive the price up. I wait to see how bidding is going. I will have a price in mind that I am willing to pay for an item. As bidding slows, I will jump in if the bid does not exceed my maximum.

When an auction house wants wide coverage of their auction, they may run it both in-person and online via a service such as Live Auctioneers or Proxibid. When the auction will run simultaneously online, the full auction catalog–including photos–is uploaded in advance of the actual live auction. Once the catalog is uploaded, bidding opens online.

I am dumbfounded when I see bids placed online before an auction begins. Peeps, all you are doing is driving the price up! It’s like bidding on a valuable eBay item well before an auction ends; you should know that serious bidders will come in at the last minute. People pay for sniping services on eBay because they want to jump in at the last second with their best price instead of bidding early and waiting for someone to outbid them.

If you watch an eBay auction for a highly collectible piece, you will often see that the price jumps in the last 10 seconds or so before the auction ends. Seasoned buyers wait until the end of the auction to avoid driving up the price.

Don’t start bidding before the auction begins or place small bids on every item “just in case” no one else bids, and you miraculously win a coveted item at an insanely low price. It won’t happen. Other collectors will notice a bid on sought-after, highly collectible items. Online auctions attract a large audience, so increasing the bid before the auction begins will lead to a higher final price compared to waiting.

Absentee bids

If you really want an item but can’t be present at the auction or follow along online as it takes place, consider placing an absentee bid. Auction houses have different ways to place and enter an absentee bid. If you want to put one and the information is outside the terms and conditions of the auction, call and ask the auction house how you can place an absentee bid and how they handle absentee bids.

There are at least three ways that absentee bids are handled. One is where a person associated with the auction house is seated in the audience, acts as the “absentee bidder,” and places bids for you. It is treated just as any other bid by another bidder. For example, if I placed an absentee bid with a maximum of $50, the person sitting in the audience would bid just as any other bidder up to my maximum of $50 and would then drop out. If I was lucky, the person bidding for me might snag the piece for less than my maximum.

You’ve probably seen scenes like this at high-dollar art auctions, where a person present is on the phone with the bidder, who is not present. The bidder approves or disapproves a bid and the person who is physically present places the bid for them.

Another way absentee bids can be handled is that the auctioneer starts the bidding where they usually would, e.g., $25. A person working for the auction house is at the computer, watching and handling online bids. Once bidding slows, that person yells out bids for the absentee bidder up to the absentee bidder’s maximum. Like the first scenario, an absentee bidder could win the item short of their high bid.

A third way I have seen absentee bids handled, which I dislike, is where the auctioneer starts the bidding at the maximum of an absentee bid. For example, if my maximum absentee bid was $50, the auctioneer starts the bidding at $50. Or if my absentee bid is $50 but another absentee bidder’s maximum bid is $100, the auctioneer begins at $100. That’s no bargain.

It is in the auction house’s best interest to get the highest price possible – both for their profit margin and for the benefit of the person who consigned the pieces to the auction house. 3

Random Considerations for In-Person Auctions

If you are bidding, don’t make any sudden movements!

I’m only half-kidding. During bidding, the auctioneer is doing the auction chant, and ringmen and ringwomen standing in the front are helping the auctioneer find the people in the audience who are bidding.

Hold your paddle high when you bid so the auctioneer can see it. Otherwise, your bid could be missed.

Once you have begun bidding, the auctioneer will look back to you to see if you want to continue to bid when a competing bid comes in. So if you are talking and you nod at a friend, the auctioneer may take that as a “yes, I want to bid,” and the bid will be placed for you. If I am doing intense bidding on an item, I usually raise my paddle high for my first bid, and then when the auctioneer looks at me for subsequent bids, I meet his or her eyes and shake my head “yes” or “no.”

If you are taking items you have won out to your car before the auction ends, let the auction staff know that you are coming back.

During a long auction, Auctioneers typically switch off from each other and take little of a break. Bidders, however, might take breaks when there is a bit of time before something they want comes up for bid. Food is often offered for sale during auctions; people take breaks to have a cup of coffee or have something to eat while the auction continues.

If you start taking iron out to your car to pack it, it’s considerate to let the auction staff know you are coming back; you’re not planning to step out without paying. I’ve never seen people fail to pay at an in-person cast iron auction, but I suppose it could happen.

Best prices are usually at the very beginning and very end of the auction.

From my observations, pricing seems best at the very start and end of an auction. At the beginning, I think people are waiting to see what kind of prices pieces will bring, and are kind of getting into the “flow” of the auction. Sometimes people simply arrive late.

Similarly, collectors may be there for a particular item. Once that piece has sold, they leave.

With long, all-day, multi-day auctions, I’ve seen the crowd of bidders dramatically thin toward the end. Fewer bidders result in better prices for you.

Karma is real.

I was at an auction once and I knew that a friend intended to bid on a Griswold large block logo EPU number 5 skillet with a heat ring. He wanted it for his collection, but I would have loved to have it to resell. These skillets are scarce, especially in great condition.

There were two offered at this particular auction; one with a lid and one without. My friend bid but did not win the first one. The second one – with lid – came up for auction and my friend was nowhere in sight. I bid on the set and won it for a reasonable wholesale price. I knew I could sell the set for much much more than I had paid for it.

Some time later my friend came back from wherever he had gone, and I gave him the piece for what I had paid for it. I would have been buying it to resell; he wanted it for his collection. My relationship with him – as well as with others in the cast iron community – was more important to me than the money.

In the grand scheme of things, the cast iron collecting community is small and your behavior is remembered.

Bring boxes and packing materials.

How are you going to get your precious pieces home? The auction house will probably have some boxes available, and sometimes some newspapers and such to wrap pieces, but they won’t have enough for everyone. It is smart to bring your own boxes and packing materials for the items you purchase.

Going to the produce section of a local grocery store in advance of the auction can be a good bet, as banana boxes are often available at no cost for the asking. You might not be the only person who has thought of this, however; the grocery store might not have any available.

You will see bidders at an auction hauling around big heavy-duty tote boxes—the ones you can buy at Lowes or Home Depot with the black containers and yellow lids. Sometimes, people (like me) will have a folding wagon that they use to transport purchased pieces to their cars.

Once in a while a strapping young person might offer to help you pack your iron or help to carry boxes to your car. If you take advantage of this service, a generous tip is always appreciated. Be nice. Nice goes a long way.

Be sure you pack your pieces carefully. Cast iron cookware is not indestructible. It is brittle and it can break if not carefully packed. It would be a shame to break a valuable piece on the ride home because of poor packing!

Have fun!

All this said, have fun!

I have been to many vintage and antique cast iron cookware auctions all around the country. They are an amazing sight to behold. If you have an opportunity, go! You will meet many other friendly cast iron enthusiasts. You may see faces you’ve seen before on cast iron hunts, but there are typically some who are new to cast iron. Their excitement is contagious.

Sometimes people get caught up in the excitement and buy much more than they intended, or pieces they didn’t even know before bidding started that they needed or wanted.

I’ve been there; I know how that goes. For me, the thrill of the hunt is half the fun!

- For example, at a July 2018 vintage cast iron auction, several of us concluded that two pieces offered (a “Griswold” Vienna pan and a “Griswold” Turk’s head pan) were most likely recasts. A few pieces were also noted to have small hairline cracks.

- If you are following an auction online, sometimes a lot will be “passed” if no one bids at the opening price.

- Auctioneers typically receive a commission, though the amount (and what is included) varies from company to company. For example, a company might charge 15-20% of total sales plus actual expenses for advertising, room rental, auctioneer services, ring men/women, cashiers, brochures, etc. Other auction houses might charge a higher percentage i.e. 25%, but include those additional expenses in that commission percentage.